Iffat Mirza Rashid, Bentley

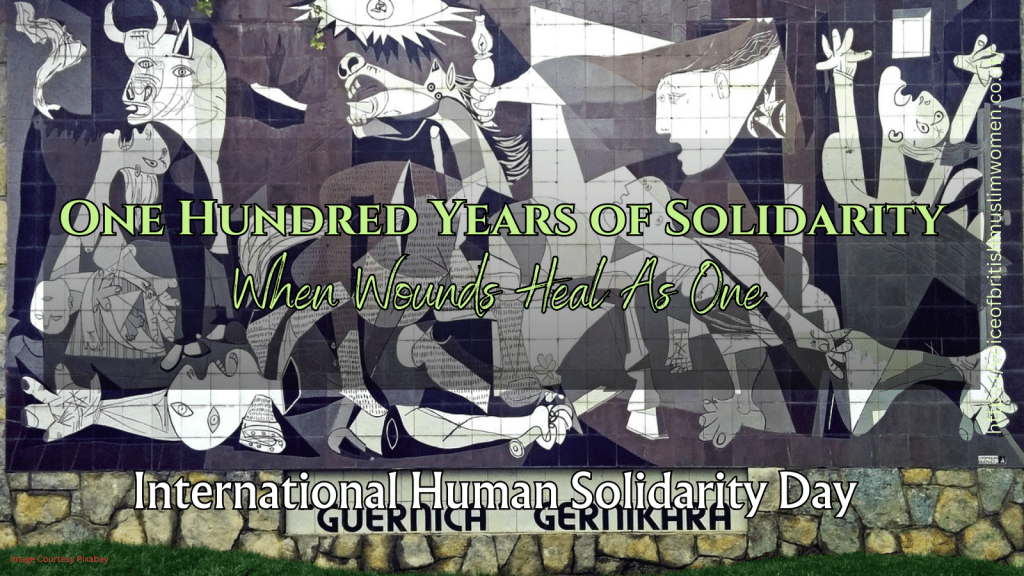

At seventeen, in the Reina Sofía Modern Art Museum, I stood before an 11 foot tall, 25 foot wide painting – the monochromatic, cubist work of art that depicted the brutal massacre of thousands in 1937, at the height of the Spanish Civil War. A room dedicated to a singular painting, depicting the distorted images of a mother’s tears, children in anguish, livestock in fear, in a chaotic and cacophonic composition, holds what is today one of the most famous anti-war paintings. Guernica. The depiction of the massacre of a small village, Guernica, in the Basque country by General Franco’s regime, in alliance with the Nazi Party who themselves were preparing for the impending Second World War, is one that bears witness to the brutality of modern warfare and human arrogance.

I was fortunate enough to travel to Madrid on a class trip. The aim was to, in that short week, improve our Spanish speaking skills, experience the culture, and to wander the capital of a country rich with centuries of history. Having learned about this painting beforehand in a Spanish lesson, I was awe-struck by its immensity, along with seeing Picasso’s sketches and drawings in preparation for this project in encased displays. The story of Guernica never escaped me. Exactly a year ago, in December 2023, the air raid sirens of Guernica blared again. Guernica was not under attack. Gaza was. For Guernica, a wound inflicted nearly a century ago was still fresh, for they say the same mechanisms of violence and oppression were inflicted on others. In an air of defiance against such mechanisms, the people of Guernica stood in formation to recreate the Palestinian flag – a message to say “we are with you”.

Whilst the original painting is housed in Madrid, a replica of Guernica also hangs at the UN Security Council, a reminder of the duty that member states have in preserving peace and in remembering our past which is marked by so much anguish and pain. Whilst there have been many opportunities to call for a ceasefire in Gaza in the last year, and despite the symbolism and imagery of Guernica, little heed has been paid by powerful nations who believe ‘might is right’. But the act of solidarity has proven to be much more powerful – in many conflicts since the bombing of Guernica, the painting has been invoked, during Vietnam, Iraq, and now Gaza, the imagery has proven to be a symbol of solidarity amongst all oppressed peoples.

I mention this one painting at length, not because it is the only expression of solidarity, that is by no means the case – but it was certainly one that opened my eyes to the fact that no wound is healed until all wounds are. Nearly a hundred years later, we are witnessing the same destruction and anguish and despite entering my late twenties now, I see myself as that 17-year-old who was so horrified at the necessity of such artwork.

As we come to International Human Solidarity Day, I am positively reminded of the power of the collective, the defiance in the face of oppression and violence that is not driven itself by violence, but by a love of humanity. It is the antidote to the arrogance and greed of the powerful. It is the love and empathy of the people of Guernica in 2023 which sends a call to the people of Gaza to bear strength and resilience. It is the people of Guernica saying “We survived, and you will too.” A power of such strength can only be delivered with the love of humanity.

The Promised Messiah (on whom be peace), encapsulated this sentiment so beautifully when he wrote ‘One should never be indifferent or apathetic to the needs of others.’ (1) Indeed, it is indifference that enables oppressors. Oppressors do not need us to hand them the weapon, they simply need us to look away as they wield it.

Solidarity expressed when indifference is demanded is indeed the difference between life and death for some. Along with Guernica, I am also reminded of the final words of the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude ‘Everything written on them was unrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more, because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth’. (2) Indeed, a most pessimistic ending to one of the 20th century’s greatest novels. However, less known is the author’s inversion of such words, in his Nobel Prize lecture which he ended with the words:

“Face to face with a reality that overwhelms us, one which over man’s perceptions of time must have seemed a utopia, tellers of tales who, like me, are capable of believing anything, feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to undertake the creation of a minor utopia: a new and limitless utopia for life, wherein no one can decide for others how they are to die, where love really can be true and happiness possible, where the lineal generations of one hundred years of solitude will have at last and for ever a second opportunity on earth.” (3)

All around us, we have reminders of what humanity has been capable of doing. Through resisting indifference and apathy, through allowing the wounds of others to be felt as though they were our own, we can indeed envision a future where we have worked towards a collective liberation from oppression. For me it is the example of Guernica, for you it may be something else, but indeed, in doing so, we can recall the power of one hundred years of solidarity.

References:

- Malfuzat, Vol. 7 pp. 105-106 Edition 1984

- One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, p201

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1982/marquez/lecture/

Leave a comment